All fun was forbidden

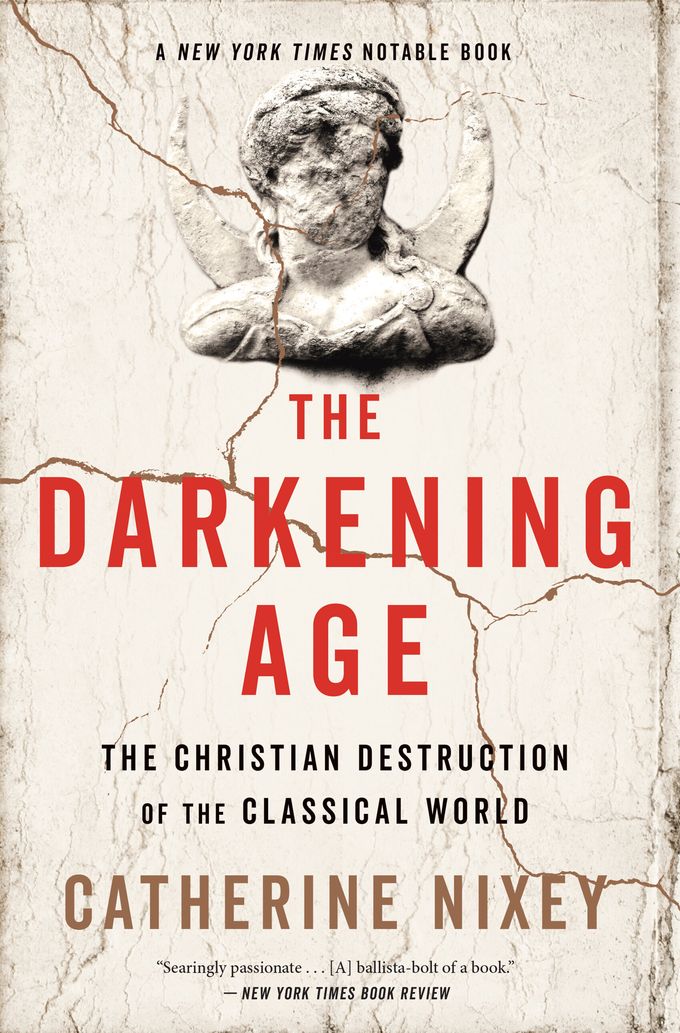

Review by Catherine Nixey, The Darkening Age, The Christian Destruction of the Classical World.

This book was published in 2017. It is extensively reviewed, page by page, by atheist Tim O'Neill on his blog History for Atheists. According to him, the book is a biased polemic that presents itself as a historical analysis but is "easily the worst book I have read in years".

The title alludes to the concept of the dark ages, coined in the 14th century by Petrarch, who complained that there was a lack of written sources from the time after the fall of the Western Roman Empire (secoli bui). Nowadays, this pejorative designation is avoided. The period today is called the Early Middle Ages. It has been completely re-evaluated by historians of our time.

Nixey grew up in a strict Catholic home in otherwise secular Wales. Her father was a monk but left the monastery during the convulsions after Vatican II. Then he met her mother, who previously had been a nun. They married, but kept their Catholic "faith in the nurturing power of the Church".

Personally, Nixey still has a positive view of her tolerant parents, while her book is a furious, if not mocking, reckoning with their Christian faith, supported by numerous examples from the early church's relationship with ancient culture. Based on an eclectic collection of facts, presented in an extensive bibliography, the presentation is unbalanced. The result is a pamphlet that does not meet academic standards, something Nixey may not be aiming for either. The method is anecdotal evidence. Life in ancient Rome is depicted in a romantic shimmer, while the Christians appear as humorless fanatics who uncritically believe in absurd and ridiculous stories. Thoughts go to the former nun Karen Armstrong, who in a series of books portrayed all the world's religions as superior to Christianity.

However, Nixey does not seem to realize that the late Roman dream world she constructs not was accessible to everyone, perhaps only to two percent of the population of Imperial Rome. The pleasure-filled luxury recommended by Catullus and Ovid for its existence depended on slavery. Humans were expendable as much as ever Russian soldiers in the assault waves in Ukraine.

For most, life was hell, far from the lustful existence depicted on the frescoes in Pompeii's brothels. The ancient pornography and prostitution that Nixey fondly describes was no fun for those who were exploited. Women and slaves instead experienced Christian morality as liberation.

Supposedly supported by Gibbon's famous The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1794), Nixey blames the fall of the Roman Empire on Christianity. Nowadays, otherwise, that way of interpreting Gibbon is questioned. The decay had already begun before Christianity was something to be reckoned with and, according to Gibbon, was more due to neglect and the luxury consumption of the ruling classes.

However, it is understandable that the change in mentality that spread through Christianity in the Roman Empire also brought about certain aggressiveness towards earlier values. Already in Acts 19:19 it is told that those who practiced sorcery "collected their books and burned them in public". The fact that many of the ancient artefacts have been destroyed, however, is more due to the ravages of time, wars and fires, as well as the fact that the local population provided themselves with building materials from obsolete buildings and monuments.

However, we can regret that they not acted as responsibly as in nowadays Budapest, where they collected out-of-date giant statues from the communist era of the heroes of work in the Szobor Park next to the Puskás Stadium and where you can view Lenin, Marx and Engels in colossal format in the Memento Park.

The transition to Christianity was gradual, largely without upheaval. Even the superstitious emperor Constantine's conversion to Christianity did not take place as suddenly as Nixey would make it seem. Soon enough, especially after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the church actually nurtured and passed on the ancient heritage. Augustine in his commentary on Genesis complains that naive Christians do not listen to science. When Pope Benedict XVI (Ratzinger) gave his celebrated lecture in Regensburg in 2006, he emphasized Christianity's dependence on Greek philosophy. He reminded that not only the New Testament is written in Greek but also the Septuagint, which is an independent textual testimony. The Pope emphasized that the Greek heritage is an essential part of the Christian faith. And those who today want to view pagan images of gods can conveniently go to the Vatican Museum.

In 529, the Academy of Athens was closed by the emperor Justinian, a symbol-laden event that Nixey overemphasizes. Long before Plato's academy had died of its own accord, and the then the Neoplatonic academy was founded as late as in the year 410. Symbolically, in the same year, 529, Benedict, so hated by Nixey, founded a monastery on Monte Cassino. From this monastery Europe was civilized under the motto Ora et Labora, directed against the ancient contempt for manual labor. In desolate places the monks founded sister monasteries, cultivated the land, planted gardens, fishponds, forges, mills and glassworks and set up libraries, all such things which are the basis of our present prosperity.

The Christian background is also reflected in such phenomena as democracy, freedom of expression and even atheism, something demonstrated by Tom Holland in Dominion, The Making of the Western Mind (2019) and Larry Siedentop in Inventing the Individual, The Origins of Western Liberalism (2014).

Nixey illuminates the encounter between antiquity and Christianity too obliquely to be taken seriously. She leaves the reader with an unanswered question: How did it come about that the cozy paganism was outcompeted by the desolate Christianity?

Anders

Brogren

Dean h.c., Falkenberg, Sweden

Sankt Lars Kyrkogata 4

S-311 31 Falkenberg

SWEDEN

Mail

to

anders [ at ] brogren.nu