When

the Security Police Agent became

President

of the Lutheran World Federation

Published in Svensk Pastoraltidskrift 13/2008

On a summer Sunday in 1987, after the service in Istorp's church, a couple

I had not seen before came up and said hello. It turned out to be Karin

and Vilmos Vajta. They had a summer place in the neighborhood.

Thus began our friendship. For several years in the summer then we met at each other's houses. The conversations revolved around many topics. Not least Vilmos liked music. When we played and sang some Hungarian patriotic songs that my father had studied during his time in Vienna in the early 1930s, Vilmos was visibly moved. After many years in exile, hearing Szép vagy, gyönyörü vagy Magyarország (You are both beautiful and glorious, land of Hungary) touched him deeply. It was also solemn to hear Vilmos read the table prayer in Hungarian.

Vilmos was born in 1918 in Kecskemét in the disintegrating dual monarchy. He was ordained a priest in 1940 in Hungary's Lutheran minority church. The following year he received a scholarship to study in Uppsala.

When first the Germans and then the Soviet Union took control of his homeland, Vilmos came to stay in Sweden. In 1944 he moved to the then Mecca of Luther research in Lund. In 1947 he married Karin. He also worked as a priest among Hungarians in the dispossession. He became a Swedish citizen and a priest in the Church of Sweden in 1949. In 1953 he became a Doctor of Theology on the thesis Theologie des Gottesdienstes bei Luther.

Then he was appointed director of the Lutheran World Federation's Department of Theology in Geneva. He arranged ecumenical conferences for Lutheran scholars to which also secular historians and eventually even Marxists were invited. He was an observer at Vatican II. In 1964, he was called to become director of the LWF's newly established institute for ecumenical studies in Strasbourg. He came to play a key role in the Lutheran-Catholic dialogue, in the work that eventually led to the Joint Declaration on Justification. After retirement in 1981, the Vajta couple settled in Alingsås, Sweden, where Vilmos died in 1998.

Vilmos was the first one who gave me some insight into the tragic fate of Bishop Lajos Ordass (1901–1978). Ordass had many contacts abroad. He studied in Sweden with Anders Nygren and was a fellow student with Bo Giertz. In the final stages of the war, he helped persecuted Jews in Budapest in collaboration with the Swedish Red Cross. In 1945 he was elected bishop of the Western Diocese of the Lutheran Church.

Bishop Lajos Ordass

He had to tackle the difficult rebuilding work after the war. More than half of the churches were destroyed. Ordass traveled around to all the parishes and small diaspora groups in his diocese to encourage and instil hope for the future. With a great willingness to sacrifice and with financial help from abroad, the reconstruction could begin. Ordass became highly respected for his work. At the Lutheran World Federation's first general assembly in Lund in 1947, he was elected first vice-president.

But by 1948 the Communist Party had outmaneuvered all other political forces. Now followed a Stalinist reign of terror with a merciless fight against "reactionary elements". One of the few who did not give in to the state threats was Ordass. Therefore he was arrested on September 8, 1948 and sentenced to two years in prison and a further five years suspended from office. The fabricated conviction was currency offence. A committee of responsibility established for the purpose within the Lutheran Church condemned him in April 1949 and declared him deposed.

With Ordass in prison, the main obstacle to confiscating the Church's schools disappeared. At this time, over half of Hungarian schools were still run by the various churches. The agreement with the state was signed on 14 December 1949 on the part of the Lutheran Church by the Bishop of the Eastern Diocese, Túróczy, who was the President of the Synod.

Two days later, Túróczy was installed as Ordas's successor in the Western Diocese. But he didn't stay there long. In line with the centralizing zeal of Stalinism, in 1952 the church's four dioceses were merged into two, which resulted in Túróczy losing his office. Bishop in the northern diocese became the Russian-speaking and pro-regime Lajos Vetö. Communist sympathizer László Dezséry was appointed bishop of the southern diocese.

A "retardation" followed Khrushchev's secret speech at the 20th Party Congress in 1956. It was a temporary liberalization. In August, the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches met in Budapest and put pressure on the Hungarian government regarding Ordass. This led to the authorities declaring the deposed Ordass rehabilitated on 5 October.

On October 23, the uprising against the Soviet-backed puppet regime broke out. On Reformation Day 31 October, in the midst of the rebellion, Ordass was reinstated in his office as leader of the Church, now as Bishop of the Southern Diocese. Bishops Vetö and Dezséry resigned. At the same time, they turned their coat to the new winds and praised the revolt of the Hungarian youth. But the timing was bad. Only a few days later the revolt was crushed. However, Dezséry later became a successful journalist and "came out" as an atheist. Túróczy was appointed bishop of the northern diocese and thus became a bishop again, now for the third time.

In November 4 the uprising was put down by Soviet troops, but Ordass was allowed to maintain his position. The church began again to flourish. Ordass was even granted permission to travel to the LWF's third general assembly in Minneapolis in 1957 where he was feted and re-elected vice president.

Back in his home country, he again began to be attacked by the authorities. Admittedly, with his starting point in the Lutheran two-regime doctrine, Ordass had not made any public statements against the regime or against communism, but he had also not joined the fellow runners or praised the "conquests of socialism". But when Vetö and the theology professor Pálfy began to attack him in the press, the regime got a pretext to again remove him from the episcopate. This happened in June 1958. Ordass was forbidden to preach. He also had no opportunity to defend himself against the public attacks he was subjected to. Travel abroad now became unthinkable. It became risky for the priests to have contact with him. He was made a stranger in his own church, lived as a private man in his apartment in Budapest and died in 1978.

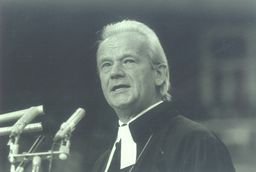

Ordass was succeeded as church leader by Zoltán Káldy (1919–1987). He was installed as bishop on November 4, 1958, the second anniversary of the suppression of the 1956 uprising by Soviet troops.

Bishop Zoltan Kaldy

Káldy came to launch "diaconal theology." According to Káldy, the Bible would be adapted to the current political order. One should act in accordance with common sense. The church would work for "political worship" and improve conditions in this world. Even the world is part of God's kingdom. According to Lutheran ethics, there is no difference between Christian and secular ethics, between work in the church and work to "build socialism in our country". Jesus' love compels the Christian to political activity, according to Káldy. However, there was no mention of sin, grace and salvation.

Káldy's theology was implemented at all levels in the church. If any priest came up with the idea of expressing doubts, he was branded and sent to some small parish in the country. In 1966, Káldy pushed through a new church constitution that was adapted to the demands of the Marxist state power.

After it was decided that the Seventh General Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation would be held in Budapest in 1984, Káldy made sure to have the internationally experienced Gyula Nagy by his side as Bishop of the Northern Diocese. Nagy made appropriate adjustments to Káldy's diaconal theology so that it could be more easily accepted in international contexts. But this theology was also criticized for the first time.

The criticism came from the internationally renowned and Sweden-based Vilmos Vajta in an article in Lutherische Monatshefte in 1983. Vajta believed that the diaconal theology lacked its own ideological core while being characterized by unconditional cooperation with the regime. They built on biblical words that were chosen in a one-sided manner. The Church had been deprived of the opportunity to criticize the abuses committed by the Hungarian state. It was allowed to criticize racism in South Africa or the United States, but when Hungarian troops entered Czechoslovakia in 1968, the church did not protest. Its newspaper Evangélikus Élet even defended Hungary's participation in the invasion. Neither Jews and dissidents who were harassed by the regime, nor those who were imprisoned because they did not approve of the communist system could be subject to diakonia. Theology had become an ideology that was not allowed to be criticized, according to Vajta.

Vajta was subjected to a furious attack by the ecclesiastical leadership set appointed with the good memory of the regime. Vajta's "slander" was nothing to pay attention to because it came from a man who had lived in the West for 42 years and who therefore had no conditions to be able to rebuke his old church.

The following year, LWF's seventh general assembly was held in Budapest as planned. It was about electing a new president after Tanzania's Josiah Kibira, who was affected by Parkinson's disease. The proposed successor was – Zoltán Káldy!

However, many delegates were skeptical and were also influenced by an open letter from Reverend Zoltán Dóka, in which he called diaconal theology "social ethical manipulation of the Gospel" and protested against the "theological terror" that Káldy practiced against the Church. Other delegates, on the other hand, saw in Káldy a bridge to the communist world.

The Swedish delegation traveled to Budapest with some pain. Bishop Helge Brattgård, who was a delegate, states in an interview with Björn Ryman, reproduced in Ryman's book Lutherhjälpens första år 1947–1997: "We felt it was important to be able to visit his [Ordas'] grave and that Ordas's successor, the controversial Bishop Káldy, was present. Káldy asked at this ceremony for forgiveness for the wrongs he had committed against Ordass. Immediately after this he turned to me and said: 'I mean this from the heart'."

Káldy won the vote, but it was not long before he was able to enjoy being the LWF's highest representative. He fell ill in December 1985 and died already on May 17, 1987. Thus, he did not have to experience how the regime that made his career possible was dissolved in the political upheavals two years later. When communism collapsed, the agreement from 1949 between the church and the state was terminated. The new government issued an official apology for the former regime's treatment of Bishop Ordass, who was thereby rehabilitated a second time, but this time posthumously.

Now the attention was again directed towards Vilmos Vajta in Sweden. He was called to an honorary doctorate at the theological seminary in Budapest. I remember how that summer Vilmos really agonized over whether he should travel there or not. He knew who they were behind the summons and he saw them more as turncoats than as honest people. At least he left in the end. I believe that he somehow saw this honorary doctorate as recognition and an end point of nearly half a century of struggle for the freedom of the Hungarian Lutherans.

* * *

Some years later this whole tragic story got a dramatic epilogue. It was revealed that the traitorous bishop Zoltán Káldy in fact was an agent of the dreaded security police ÁVO/ÁVH! The person who revealed this is Tormod Engelsviken (b. 1943), professor at the Menighetsfakultetet in Oslo, together with the hungarian-norwegian pastor László Terray (1924-2015). Since 2003 they studied the relationship between the Lutheran Church of Hungary and the ecumenical organizations, especially the LWF, doing archival studies in Budapest and Geneva. They then found out that Káldy already in 1958 was recruited as an agent , even before he succeeded Ordass as bishop. He received the code name "Pecsi" and had regular meetings with his clients in various apartments in Budapest. His file in the security police's archives comprises 1200 pages.

Káldy reported on various personnel matters in the diocese and on how Ordass and his associates were removed. He also reported individual conversations he had with priests who sought him out. He gave his characterization of the priests, written reports on the mood within the church and provided information on the inner life of the diocese. Furthermore, he described his trips abroad and the conversations between four eyes he had during these trips.

The bishop of the northern diocese, Gyula Nagy, he too was an agent. When the security police used to meat the two agent-bishops in secret apartments, they received their instructions. They would not only report about Hungary but also infiltrate international church work and exert influence in the direction desired by the regimes in Eastern Europe. It must be said they were very successful.

Engelsviken focuses particularly on the relationship with the Norwegian Church. When Káldy was elected president of the LWF in 1984, the Norwegian delegation was divided. One of Káldy's advocates was the church bureaucrat Gunnar Stålsett. He was then elected LWF's general secretary and worked closely with Káldy. Later, Stålsett became a controversial bishop in Oslo.

* * *

This is, in short, the sad story of a manipulated Lutheran church in an ideologically monopolized state. That's what can happen when a church loses its integrity. It is a cautionary example.

Anders

Brogren

Dean h.c., Falkenberg, Sweden

Sankt Lars

Kyrkogata 4

S-311 31 Falkenberg

SWEDEN

Mail to

anders [ at ] brogren.nu